Revision Checklist for Essays & Short Stories

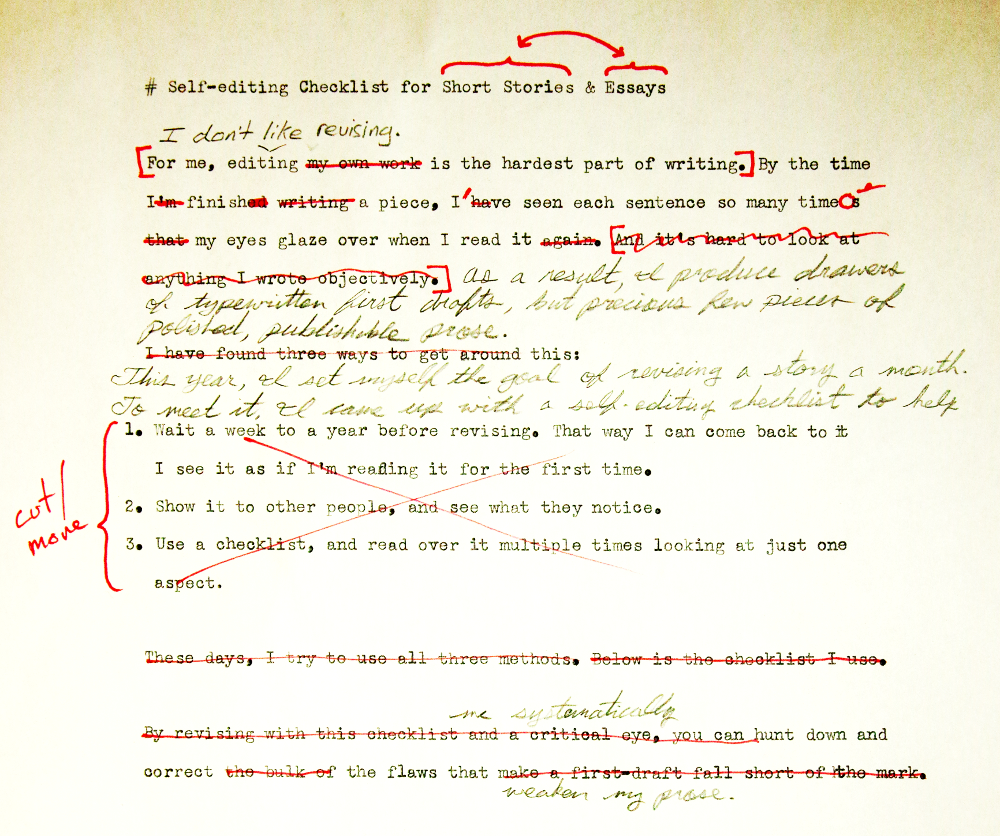

I don’t like revising. By the time I’ve finished writing a story or essay, I’ve seen each sentence so often my eyes cross and glaze over when I try to reread and revise it for the nth time. The result? My draft-to-publication ratio is about 300:1.

This year I set myself the goal of revising a story each month. To meet it, I needed a strategy for tackling intimidating revisions; a map showing how to get from first to final draft.

I searched for revision and self-editing checklists online, but didn’t find any that seemed sensible. So I wrote my own. Then, I decided to get a bit meta and use the checklist to revise the checklist, and publish it here for the benefit of my fellow shirkers.

The Self-Editing Checklist

Content

- Don’t waste the reader’s precious time on earth, or yours. Why did you write the piece? Is what you’re trying to say worth saying? Does the piece say what you are trying to say. If you’re investing effort revising the piece, you’ve already ticked off this checkbox.

- Make sure the piece has a positive emotional and/or intellectual effect on the reader. If you write horror, you may want to strike discord in the reader’s heartstrings — but even if the content isn’t positive, the piece should benefit the reader in some way. Otherwise, why would they bother to read it?

- Double check your logic: implausibility loses readers faster than you can say Hack Robinson.

- Non-fiction: check that your assumptions about the subject are correct, and that your conclusions follow logically from the starting point.

- Fiction: check for plot holes, bad science (real or invented), handy coincidences that move the plot while the characters sit around and watch, and characters doing things that are out of character to move the plot.

- Check that the facts are, in fact, factual. It saves a lot of embarrassment later on.

- Make it as easy as possible for the reader to understand what you’re saying, and do your best to counter the effects of the “Curse of Knowledge”.

- Make sure the piece is complete and gets across what you’re trying to communicate.

- … and that the opening pulls the reader in, arouses their curiosity, and makes them want to know more.

- … and that the ending is strong, and pulls in and resolves as many narrative threads as possible.

Structure

- Make sure the piece flows well, and scene (fiction) or section (nonfiction) transitions are smooth and logical.

- Put first things first so that the reader knows all they need to know to understand what they’re reading.

- Adjust paragraph and sentence length to match the pace of the content.

- Cut needless words, sentences, paragraphs, and sections.

Style

- Match tone to content.

- Match pronouns to content: Is it a personal narrative (I did this, I thought that)? A sermon (you should do this, you should do that)? A sermon masquerading as objective analysis (one should do this, one should think that)? As you have probably noticed, this is a sermon.

- Don’t be a showoff. Showing off — whether with big words, excessive intellectualism, or beautiful but superfluous prose — gets in the way of good writing. Show off by not showing off, and, instead, getting straight to the point.

- Towel off your attitudes. Logic is more persuasive that ranting.

- Cut the parts that you’d be embarrassed to read aloud to your mother. Mother doesn’t have to agree with it, or even like it, but it shouldn’t embarrass you to read it to her. By writing even the most controversial pieces in such a way that you wouldn’t be embarrassed to read them aloud to your mother, you’ll probably reach a wider, classier audience.

- Make sure the tone isn’t too dry or too wet. The Buddhist idea of The Middle Way applies to writing, too. Neither stiff nor overly jocular, neither brusque nor logorrheic, good style is often almost indistinguishable from no style at all.

- Read it aloud, and rewrite the parts that sound unnatural.

Polish

- Prefer short, strong, precise words you know the exact meaning of. (Also: If you use a word the reader may not know without defining it, try to make it possible to infer its meaning from context.)

- Use passive voice deliberately.

- Make sure modifiers serve a purpose. (Adjectives, adverbs, qualifiers, etc.)

- Tone down the superlatives and exclamation marks! They are most often used as crutches to keep weak sentences from falling flat. If what you write is true, and your sentences are strong, you shouldn’t need to ram your point home.

- Use spell-check. Defiantly a god idea.

- Run it through a grammar-checker such as LanguageTool (free, open-source) or Grammarly (paid).

- Consider using a “prose linter” such as ProseLint (free & open-source, available online and as an editor plugin), Write Good (free & open-source, available as an editor plugin), Hemingway Editor (freemium, available online and as a desktop app), or similar.

- Format the piece for its intended destination. Check the submission guidelines for the publication(s) you’re planning to submit to. Using real em-dashes (—) instead of hyphens (--) and “smart” quotes rather than "straight" quotes is a nice touch.

- Show it to at least five friends, and incorporate useful feedback in your next revision. Early readers are precious; thank them and make them a cup of tea.

How to use this checklist

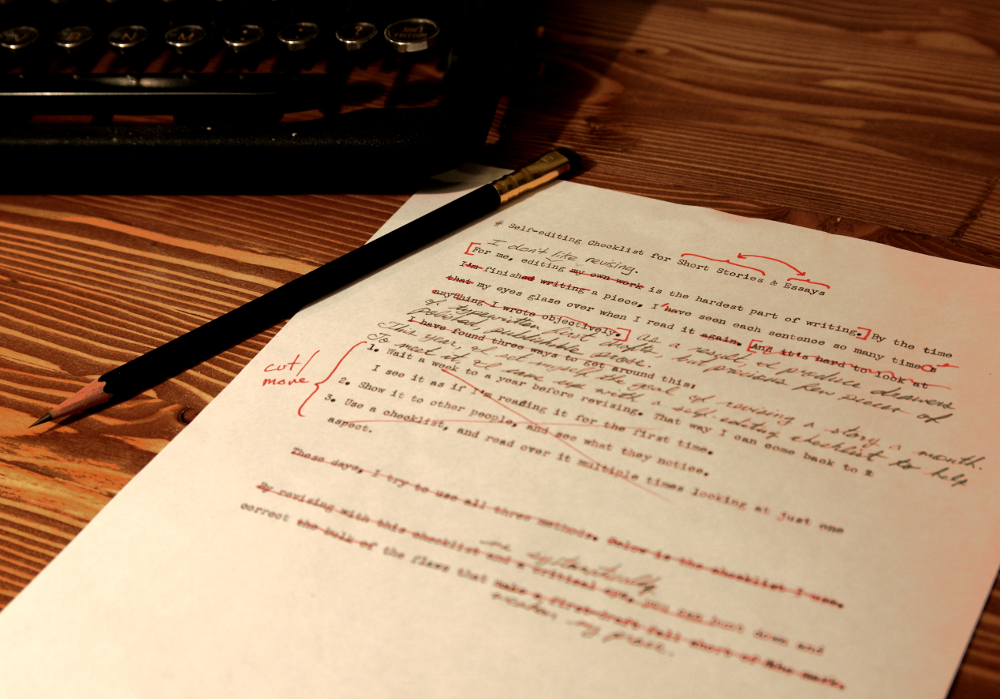

I usually show the piece to other people and ask for feedback, and take notes of their suggestions. Next, I make a “revision plan” that lists the problems beta readers (and myself) have unearthed, along with possible solutions. Then, after waiting a week (or a year) in order see the piece anew, I read through it and update the revision plan as necessary. Finally, I make a cup of coffee — or several, depending on the length of the piece — and work through the piece, referring to my revision notes and this checklist.

The structural changes in the first two sections of the checklist often require significant additions, cuts, and rewriting. Make them early in the revision to avoid cutting prose you’ve already buffed-and-polished. I refer to the second section throughout the revision, but wait to start the third section until I’m done with most of the rewriting and rejigging.

Make it your own

You’re unique, just like everybody else. So here’s a plain-text version of the checklist you can customize for what you write and how you revise: revision-checklist.txt. Make it your own! And when you’re done, jump in the comments and let me know what you changed.

Now print your piece (after clearing the paper jam at tray 1), open the checklist, and get to work! Put that writerly scowl on your brow; cap and uncap your pen so you can hear that tremendously-satisfying click; make some illegible scritches; crumple the marked-up manuscript and hurl it across the room, just missing the garbage can; pick it up off the floor and beleaguer it some more; come up with a hilarious pun; revel in your incomparable wit for a few minutes, then come back to your senses and cut it. Type in your edits, send “[TITLE] final FINAL.doc” to the printer, and repeat … and repeat. Happy editing!