Who will own Mars?

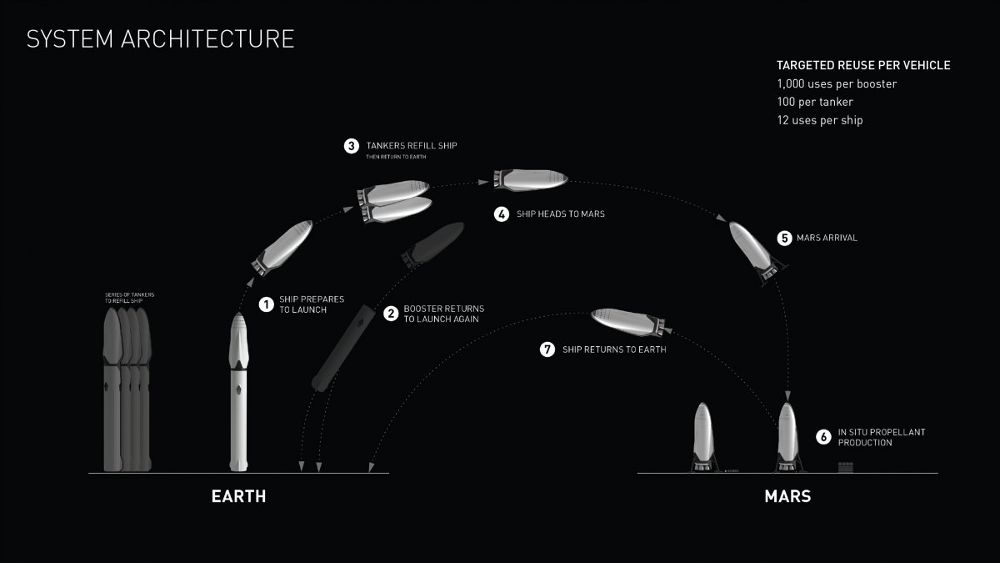

Elon Musk is planning to colonize Mars. If he succeeds, it could be one of the most important changes in human history. And, based on the surprising success of his previous ventures — including Zip2, PayPal, Tesla Motors, and SolarCity — it might be foolish to dismiss Musk’s plan.

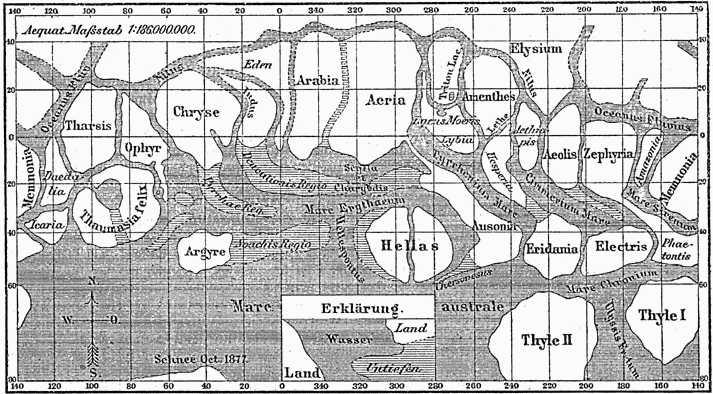

There has been a lot of hype about Mars, beginning with the Schiaparelli’s illusory observation of Mars “canali” (mistranslated from Italian to the English as “canals”[1]) in 1877 and culminating in the media hyperventilation over Musk announcing, at the 67th International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, his plan to send cargo to Mars in three years and colonists in ten.[2]

The prospect of my generation reaching Mars has fired up the popular imagination about interplanetary spaceflight in a way not seen since the Sputnik and Apollo missions six decades ago.

Everyone’s excited about rockets to Mars, and each SpaceX launch brings that dream closer to reality[3]. Musk and others are putting a lot of money and brainpower on the technical problem of getting people to Mars. Less sensational topics, such as surviving on Mars, receive less attention — but plenty of money and serious thought, because there’s no way to get around them.[4]

But there’s another important question which isn’t getting much attention:

Who will own Mars, and how will it be governed?

Does Mars belong to the people who get there first? To the highest bidder? To all the people of Earth?

Does Mars belong to Earth, or does Mars belong to Mars? Does it belong to the Sun? To the Martian microbiome, if there is one? (What are the indigenous rights of microbes, I wonder?)

Who will be in charge of Mars once the colonists arrive? If Mars turns out to have valuable resources, who gets them? And if a Mars colony is to govern itself, what kind of government would it have?

The Mars colonization project is driven by the ultra rich. And those who want to stake their claim on Mars may rather the rest of us didn’t think too much about the little problem of who owns the planet next door, and why.

Compared to most tech entrepreneurs, or most billionaires, Elon Musk seems to be doing a lot of good — he’s been pioneering (and funding) electric transportation, clean energy, and more prudent approaches to AI research. Now, he wants to backup the human race. But others in the same club may not be so altruistic — and may put business interests, such as mining Martian resources, ahead of good governance.

When it comes to governance of a Martian colony, the first question is this: will Mars be controlled from Earth, or from Mars? Initially, running Mars from Mars will probably be impractical. There will be too few people, they’ll still be dependent on Earth, and they’ll have their hands full surviving.

Earth-based control of the Martian colony could run the gamut from first-come-first-served resource extraction, to some kind of bureaucratic transitional governing body dispensing resource and settlement rights, to a more carefully regulated “commons.”

But, immediately upon the establishment of a stable colony, the interests of the Martian settlers will begin to diverge from those of their terrestrial bosses, just as they have in Earth’s colonial past. To not put in a plan for transition to self-government would be to risk disgruntlement, and, eventually, revolt.

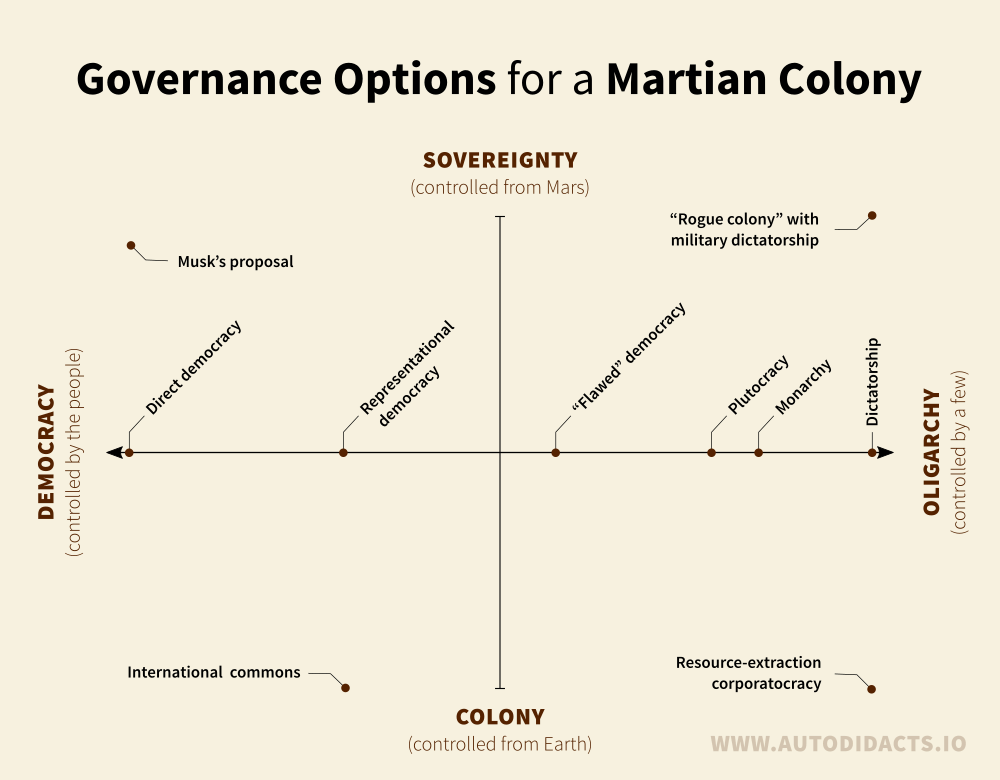

Yet, a self-governing planetary neighbour presents its own challenges. There are plenty of scenarios that could lead to a “rogue colony” of one kind or another that would be, if not a military threat in the short term, at least an annoying and potentially inconvenient political situation.

And then there’s the form of governance, regardless of where it’s controlled from. We have all the options that we’ve tried here on Earth (such as monarchy, theocracy, dictatorship, plutocracy, and representative democracy), few of which we’d want to repeat, as well as possibilities we haven’t yet imagined.

Let’s plot a few of the possibilities to get a better look at them:

In the lower left we have Mars as an international commons — neutral territory shared by all Earth’s nation-states. Antarctica is the closest analogue I’m aware of here on earth, and it’s not that close. (When we discovered it, we didn’t know it was loaded with natural resources, and I suspect this fact, along with the fact that it’s an unwelcoming hunk of ice, made it possible to put such peaceful and ecologically-responsible treaties in place. The same can’t be said for Mars.)

Musk has mentioned some sort of internet-facilitated direct democracy[5]. A direct democracy could be a way to mitigate some of the weaknesses of human nature without altering human nature itself. Whoever goes to Mars will bring themselves with: their entire cultural inheritance (beliefs, prejudices, and so forth) will go along for the ride, and so will human nature. That’s the problem: wherever we go, there we are. But as far as politics goes — and it only goes so far — direct democracy may be as good an option as any.

We have a long history of bad governance, war, corruption, injustice, and inequality. We’ve run through the laundry list of possible political problems more than once. If we don’t re-think our approach to governance before we colonize Mars, we risk repeating the most sordid parts of our history here on Earth, and Mars inheriting our intellectual, moral, and political diseases.

Musk proposes Mars as a “backup” for humanity, but, despite the apparent prudence of the idea, a second planet full of humans also doubles the chance of planetary-scale catastrophe. These concerns may seem too far-fetched and too far-future to be worth worrying about, but I think they’re worth considering because the choices being made now will have major ramifications for a Martian future. We’re having plenty of trouble here on Earth. Interplanetary conflict — human or microbial — is the last thing we need[6].

| Situation: | Options for conflict: | Options for interplanetary conflict: |

|---|---|---|

| Humans stay on Earth | way too many | ~0 |

| Humans colonize Mars | way too many × 2 | ~1 |

This is the fear-based, reactionary reason for figuring out Martian governance. There’s another profoundly hopeful reason: Mars could be an opportunity to get governance right. For once, we can do what it takes without bloodshed or revolution, because nothing needs to be overturned.

Maybe we need a new political system. Maybe the solution is a lie detector, an empathy test. Maybe it’s mandatory meditation. Maybe the solution is a new self-improvement webinar that would keep the less altruistic aspects of human nature in check. Maybe we need to build A.E Van Vogt’s Games Machine.

When the question first occurred to me, I figured I’d be able to come up with a solution. The more I thought, the more thorny the issue became: it is now clear, to my great disappointment, that I don’t know how to govern Mars. But I think it’s our collective responsibility to try to ensure, in whatever way we can, that Mars is governed well. We’re members of the human race, and the human race is trying to colonize Mars: a lot is at stake in how this project works out. Which is why the rest of us should do what we can, even if the closest we’ll get to governing Mars is thinking about it, talking about it — or writing an essay and casting it adrift in some internet backwater.

When it comes down to it, I think many of the problems we’ve had on Earth are due to human nature. But our societies reward some aspects of human nature, and ignore others. Maybe we can change ourselves from the outside in. Maybe we need to change the world from the inside out. Maybe we need to do both.

Thanks for reading. If you have a question, an essay, or a grammatical axe to grind, leave a comment below. If you can say it in under 140 characters, you can find me on twitter. Send me an email if you want to talk without (too much of) the world watching.

A more accurate translation of Schiaparelli’s “canali” would be “channels”, or maybe “grooves”. According to Popular Mechanics:

Schiaparelli's canals went viral because of a mistranslation. Instead of its literal meaning of marks or grooves, “canali” in English became “canals,” suggestive of water, life, and intelligent intervention in the Martian landscape.

My own investigation involved the internet: Google translate (English → Italian) translates “canals” to “canali”. But switch the direction (Italian → English) and Google translates “canali” to “channels” — as do Bing & Yandex. ↩︎You can watch Musk’s full 2016 IAC presentation at spacex.com/mars. ↩︎

With the exception of the Falcon 9 that blew up on the launchpad. Initial talk of sabotage has been dismissed, and the incident has been traced to a breach in the cryogenic helium system of the second stage liquid oxygen tank. That said: had it been sabotage, there could be other delays to the Mars colonization project… ↩︎

There is still a lot of work to be done on this project, or course. Most of the experiments I’m aware of, including Biosphere 2 and BIOS-3, while not abject failures, have fallen short of the mark. There have been many partial simulations of the Martian environment, some of them fairly long, but long-term closed-ecosystem experiments have (understandably) been few and far between. However, I may have missed other more promising efforts. ↩︎

More on that in The Verge’s article, Elon Musk thinks the best government for Mars is a direct democracy (He has talked about his ideas in other interviews, as well.) ↩︎

I’m not trying to fear-monger: interplanetary war is not likely in the short or medium term. But that doesn’t mean we can safely ignore it.

The stage on which interplanetary relations will be played out in the future is being assembled as I write this. The structure of the initial private-public partnership will have a huge effect on future relations between planets. And what are the possible consequences of heavy resource extraction in the early colonial days? Would it increase the probability of unpleasant interplanetary relations in the future — whether in the form of an independence revolt on Mars, or a full on war (and the first seems more likely)?

I’m no expert, but given that almost every nation state on earth has fought with its neighbours at some point in its history, with devastating consequences for both, is it wise to assume the rules of power and politics will have magically changed by the time a Martian colony reaches independence? I don’t think so.

↩︎